- Home

- Amanda Hale

Angela of the Stones Page 10

Angela of the Stones Read online

Page 10

When he arrived in Madrid he was greeted by a buxom red-haired hostess who took him in a taxi directly to Hotel Catalonia Atocha, a luxury downtown establishment, close by, the señorita told him with a rise of one sculptured eyebrow, to El Prado, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Palacio Reál and the Sabatini Gardens. ‘What about your local cuisine?’ Aragón inquired. ‘This is my special area of interest.’

That night he was escorted to La Barraca where, his friends told him, he would experience the best paella in all of Madrid. And they were not kidding! Aragón’s eyes popped as a gigantic cast iron pan was set on the table before him, sizzling with shrimp, mussels, squid, chicken, chorizo, peas and tomatoes, all jostling for purchase on a moist cloud of fragrant saffron rice. ‘Ha! We can only dream of this in Cuba,’ Aragón said, inhaling the aroma. ‘¡Mi primera paella! I am a virgin.’ With these humble words he plunged the tines of his silver fork into a plump shrimp.

There were many more trips to Spain, and several more books, each one financing the next journey. The man who had trained as a historian became in fact more of a cultural commentator, though El Museo Matachín remained his calling card with its increasingly bored staff and its yellowing grass surround into which the canons sank centimetre by centimetre while Aragón grew fatter and fatter. With his corpulence came an increase in his reputation. Who in Cuba would question a man of such girth? Everyone knew that his belly signified success. ‘All those trips to Spain!’ they would exclaim, ‘He’s eating well, and they must give him money, look at his wife, she’s a gordita too.’ Beneath the tone of jealousy lurked a profound respect, for Aragón was one of their own, a Baracoeso. The townspeople felt they shared his success, if not with their bodies, then at least in their dreams. They loved to see him striding about town and barely noticed his declining mobility as he slowed to a waddle, then struggled with a cane, until one day the manisero asked, ‘Where is Aragón? I haven’t seen him on the street since Año Nuevo.’

‘He must be in Spain,’ answered Eugenia who, like Godofredo, was on the street every day, so she would know. ‘He will be there,’ she said confidently, ‘eating paella for all of us. Give me a cone, Godo, I’m hungry,’ she said, pretending to drop a coin into his bolsa, winking at him.

When Aragón thought of Spain it was indeed paella he lusted for. Business was good, in Madrid, Barcelona, Sevilla — he had travelled all over for many years and had sold hundreds, no thousands of his coffee table books to an ever-growing circle of Spanish colleagues and institutions — but in the end it was the food he travelled for and it was to La Barraca that he always returned, sometimes taking a taxi directly from the airport. He had tried all the best paellas in Madrid — at Casa de Valencia, at El Caldero, Alhambra, El Buscón, El Tigre . . . He had sampled paella at Bosque Palermo in Barcelona, at El Choto in Cordoba, at Paella Sevilla — but nothing matched that first sight of plumply naked shellfish, that first taste of spicy steamed mussels, that virgin experience of a completely satisfied gut filled with saffron rice and seafood. He had to return, just one more time, even though he could barely walk now. He booked his flight from Baracoa to La Habana, and from there directly to Madrid, and sent his son to pick up his tickets from the Havanatur office on Calle José Martí. When the day of his journey dawned he took a taxi from his house to the Gustavo Rizo airport where he had requested a wheelchair to transport him across the tarmac to the small plane that made the twice-weekly domestic flight north to La Habana. But there were no wheelchairs available and though the driver and his friends managed to extricate Aragón from the back of the taxi, over the curb, and through the airport building, they were unable to maneuver him across the wide expanse of tarmac to his waiting aircraft.

Hipólito looked up into a clear sky, the blue of his Spanish eyes disappearing into its expanse. Why couldn’t he simply spread his wings and transport himself across the Atlantic, across Europe, and into his usual chair at La Barraca. His only desire now was for la ultima paella. ‘Just one more, oh Mami grant me just one more, please . . . please . . . por favor, one more paella for your little Popo.

MIAMI HERALD

December 18, 2014

Tito’s face flushes with anger as he picks up the newspaper from the front step and sees the smug face of Raúl Castro staring up at him. Beside Castro, unbelievably, stands Obama with his mouth open in mid-speech, his hands raised in an earnest gesture.

AFTER HALF A CENTURY, A THAW IN U.S.-CUBA TIES, the headline reads.

Beads of sweat break out on Tito’s wrinkled brow, but he can’t help dredging up a phlegmy laugh when he sees the horns on Castro’s forehead, drawn with a blue ballpoint pen! Despite his laughter a turmoil of emotions battle in his chest as he turns and lumbers towards the kitchen, his bare feet slapping heavily on the tiles. He throws the newspaper on the table, swallows a dyazide capsule and breathes deeply to calm himself as his doctor has instructed, then he turns on the television. Rubio is being interviewed on FOX News. Surely he must be outraged at this, Tito thinks, but no, Marco Rubio, ever the cool politician, maintains his calm exterior. ‘Still trying to pass himself off as a presidential candidate,’ Tito mutters to himself, ‘But he doesn’t have the balls it takes.’ Rubio has already served several years as a Republican junior state senator, gathering considerable support with his pro-life/ climate-change-denial platform.

‘The President has no right to take this executive action,’ Rubio says in his infuriatingly mild manner. ‘Neither the Senate nor Congress has approved his illegal action. As incoming chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s Western Hemisphere sub-committee, I will do everything in my power to block these reforms.’

‘¡Coño! ’Tito explodes. ‘Mario lacks charisma in spades. I could be listening to a prissy school marm! ¿Por qué no puede hablar como un verdadero Cubano, con pasión?’

He slams the remote down and pads over to the kitchen counter to pour himself a second cup of coffee. Blanca is still asleep. Tito’s always been an early riser, even during his childhood in Matanzas he’d be up and out playing before the household stirred — except for the muchacha who started work at dawn — and he would stare up at the rustling leaves of las palmas reáles, caressing their trunks with his little hands. His own kids are long gone, Eddie in Manhattan pursuing his career, Julia in upper state New York with that dumb-ass husband of hers, raising the nietos. It’s just him and Blanca rattling around in their ranch-style bungalow. Gracias a Diós he has his work, his air-conditioned office to go to every day. But it’s too early yet.

Tito spoons more sugar into his coffee. The blonde with the tetas grandes is wrapping up her interview with Rubio and faces the camera to announce that Republican Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen is unavailable for a studio interview at this moment but she has commented over the telephone that Obama may have broken several laws by acting unilaterally, including the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996, the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992, and the Trading with the Enemy Act. When FOX turns to sports Tito mutes the chica.

Gone are the days when he’d dreamed of a Cuban President for the United States. He used to believe in the possibility of a bilingual US with strong alliances between Florida and California — between Cuban and Mexican immigrants, Puerto Ricans and Guatemalans, Venezuelans, Bolivians, Chileans, Colombians and Hondurans . . . ‘El español es el segundo idioma más hablado,’ he says aloud. ‘Forty-five million Spanish speakers across this continent — and forty percent right here in Miami . . . ’ he prods the kitchen table with his forefinger, ‘where we have a rainbow of Latino immigrants. Thirty-seven percent in LA, thirty-six percent in San Antonio Texas, seventy-two percent in El Paso Texas, and . . . ’ Yes, it is his old electorial dream-speech, and he would have given as an example Canada, a bilingual country despite the fact that only twenty-two percent speak French. He’d done his research even though Americans knew nothing about Canada except that it was covered in snow, causing the older inhabitants to escape to Florida, especially the

Francophones, who are more or less close to the sunshine state.

Tito’s eyes narrow as he imagines the wraparound effect on a broad map all along the southern frontier from coast to coast — California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas — states which used to belong to Mexico, as well as parts of Wyoming, Colorado, Oklahoma and Kansas. ‘We deserve to run the country!’ he booms, surprised at the force of his own voice in the early morning quietness of his shaded bungalow. ‘We are Latinos,’ he hunches, whispering to himself, ‘the second largest language group in the world. And now look who we’re governed by.’ He slaps the open mouth of Obama on the front page. ‘And look who’s our only prospect —’ he says, gesturing towards the TV screen where Rubio is mouthing silent words — ‘Mario of the dynamic personality. ¡Coño!’

When Tito opens up the newspaper to skim through the rhetoric of the Castro-Obama speeches his eye catches a sinister piece of information —

A U.S. delegation quietly travelled seven times to Canada in 2013 and 2014, coming for meetings that covered a swap of prisoners and the re-establishment of diplomatic relations. “I don’t want to exaggerate Canada’s role,” the prime minister said, “We facilitated locations where the two countries could have a dialogue to explore ways of normalizing their relationship.”

‘¡Mama huevo!’ That smug journalist must be laughing at him today. She’d been so inquisitive, una inocente with her wide blue eyes — Cuba? the embargo? the fate of Allan Gross and the Five? . . . She was probably a spy herself, probing him for details of CANF’s agenda. Claro — he began to realize, she seemed to know a little too much about the Cuban American National Foundation — its beginnings in 1981, its affiliations, the office address and phone number — but they’d moved to new offices on Calle Ocho so she’d had to persist in order to find him.

‘Your phones are not working,’ she’d complained. ‘The custodian at the old building redirected me, but I had to walk two and a half kilometres in this heat.’

And I was a caballero, Tito thought indignantly. I invited her into my office, offered her a glass of water, a comfortable chair.

‘What do you think will come of this proposed exchange of prisoners?’ she’d asked, ‘Could it really happen, the release of Allan Gross in exchange for the remaining three of the Five Heroes?’

‘Heroes?’ he’d thundered. ‘My god, those men are criminals, murderers!’ And he’d explained it all to her, only yesterday. ‘They were responsible for bringing down a Brothers to the Rescue plane in ’96,’ he’d said. ‘Four innocent men killed trying to carry out a humanitarian quest! Those traitors will never see their freedom, especially not the ringleader. He’s serving four life sentences.’ It was all coming back to him now, like the memory of an oasis on a hot afternoon. The cool air of his freshly painted office . . . her big blue eyes . . . But he’d been fooled, that oasis was a mirage like you see in the movies, false pictures created by shimmering heatwaves. When she’d asked about Las Damas de Blanco, pretending to know nothing, he like a patsy had told her about Berta Solaire’s visit to Miami for training in self-defence, about the ladies’ peaceful protests all over Cuba, with their arms full of gladiolas. She pretended to be shocked when he’d told her about their imprisonment in Havana. And oh, how sneakily she had manoeuvred her way into his personal story.

Blanca’s heavy footsteps — he feels their vibration — his hearing is not so good these days. He’ll pour her coffee in a while. She always takes her time in the bathroom, showering, perfuming, beautifying herself for the day. First, he needs to settle his mind. His temples are throbbing. No more coffee for me, I’m already over my limit. One cup a day, the doctor said. If you must. In the morning. He sighs and stretches, fills a glass with filtered water and walks out to the back patio where a yellowing patch of grass is just beginning to receive the sun. It’s early yet, but his wife is up and this historic day has begun. All around him the neighbourhood is awakening, he can feel it, the subtle sounds and movements. Soon the cars will be revving up and backing onto the streets, dogs barking and children yelling at each other on their way to school.

He had told that inquisitive periodista about his family’s flight from Matanzas in 1962 after the nationalization of their land. ‘We lost everything,’ he said. ‘Our land, the house, our money. You can’t imagine the stress. Every night we lay in bed listening for a knock on the door. And when we reached Miami, we were waiting and waiting for Papi to come. I was fifteen years old, and I didn’t know if I would ever see my father again.’

‘Do you go back?’

‘I will never return to Cuba. My life is here. I am a Cuban American.’

‘But wouldn’t you go back if the embargo ended? With papers you could reclaim your land.’

¡Coño! The devious bitch! She’d known even then as she’d asked the question. And he had admired her, not a jovencita certainly, but passably attractive — well-preserved, with an interesting accent, and un perfume seductor that had lingered on his shirt. He’d been completely taken in and that made him even angrier than today’s disastrous news. ¡Dios mío! This changes everything. Tito doesn’t know what to think. Obama can’t end the embargo. A Republican-controlled Congress won’t allow it. How were we to know that this uppity negro would turn into a dictator like Castro, taking matters into his own hands, bypassing Congress, the Senate, the House of Representatives?

‘The so-called embargo means nothing,’ he’d said, wagging his finger at that cunning blue-eyed fox. ‘The Castros use it as an excuse for all their failures of government. They used it to get Soviet support, they blamed it for their so-called “Special Period,” while the real problem is Fidel Castro and his stubborn pride. He’s the one who closed the door. The truth is,’ Tito remembers leaning across his desk into the cool breeze of his air-conditioner, ‘The US is the biggest provider of food supplies to Cuba. But we don’t give credit like Venezuela and those countries that want to invest in a communist regime with a disastrous history of human rights abuse. We demand cash.’

‘And your property in Matanzas?’

‘Impossible to reclaim, even with papers. The Castro regime will continue long after Fidel and Raúl are gone. Even now they’re planting strategic leaders in government and industry. They’ve been very careful to train their acolytes in their own dictatorial ways. Our only hope is that the new generation, without blood on their hands,’ he’d emphasized, ‘will be . . . ’ Her mouth was opening with yet another question, but Tito had — yes, he must have sensed something even then, his blood pressure rising, a warning, a sense perhaps that his words might be repeated somewhere, even in print — he had stood up with an apology — his work, the recent move, so much to do, of course she understood. He’d stepped out from behind the fortress of his desk and kissed her on both cheeks, chastely of course, something to feed his fantasies . . .

Tito hears the murmur of the television. Ah, Blanca must be up and dressed, in the kitchen already. Just wait for it. She’s watching the news, and she’ll soon come running with an earful for him. He slumps into his sagging deckchair and closes his eyes, then it all comes flooding in — the sound of his mother’s chancletas slapping the tiled floor as she bustles about the house, the sodden squelch of wet cloth as the muchacha washes their clothes in the pila on the back patio, the soft intimacy of Mamita’s voice as she leans down to whisper to his father, and that glimpse of her breasts swinging loose inside her blouse. His body stirs with memory and, strangely, Tito feels close to tears. What is this? he wonders. I’m an old fool. The sound of rain pouring off the roof after a squall is so immediate that he opens his eyes, thinking it’s real, but there’s no rain, only another dry Miami day with a cloudless sky, still pale, yet to claim its colour. ‘Maní, maní,’ he hears — the peanut vendor’s voice in the distance . . . Tito’s heart swells and he is a child again running downtown on Calle del Medio with a peso clutched in his hand, Mami calling after him, ‘¡Tito, ven aquí, Tito, escuchame!’

&nb

sp; Blanca is calling him. He tries to answer but his constricted throat won’t let him. Cuba, mi Cuba, A solo 358 kilómetros de distancia. Will I ever go back to my country? Yesterday he said a categorical no, but today everything is different. Who is he now? He’s a Miami Cuban married thirty-six years to a Miami-born Cuban girl. He had married Blanca on her twenty-second birthday. Qué hermosa chica, caliente al trote pero inocente. They were a good match. But would she go with him? No. She’d never been to Cuba. It meant nothing to her. For Blanca Miami was Cuba. And the kids? True blue Americans, born and bred. They had nothing to look back on. When he spoke of his youth in Matanzas their eyes glazed over. Only forward, forward, that was all his son cared about — “going forward” — that stupid phrase parroted by all of corporate America — “Our company expects to make a profit going forward; We don’t expect any layoffs going forward.” ¿Qué diablos significa? And what the hell will it mean to be a Miami Cuban if there’s no more rift? I’ve built my career on that fault line, so have we all — Ros-Lehtinen, Rubio, Mario Díaz-Balart — and just about everyone on the Republican side in this state. What will we do now for our political and economic welfare? Obama has flouted the power of the Senate and the House of Representatives; he’s dismissing the voice of our clan, us Cuban Americans.

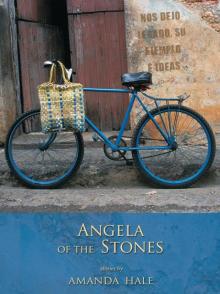

Angela of the Stones

Angela of the Stones