- Home

- Amanda Hale

Angela of the Stones Page 2

Angela of the Stones Read online

Page 2

Forbidden to speak at the Mass, the little Italian padre published his intended speech in the monthly church bulletin under the title ‘La marginación de la primera ciudad de Cuba.’ When Aurelia read it her resolve to emulate Luigi surged. She had begun to write messages to herself in the privacy of her room in the small house she shared with her two widowed sisters on Calle Primero de Abril. She had printed on scraps of paper — SEREMOS COMO EL CHE — so that, if they were found, her secret desire, to be not like Che but like Padre Luigi, would not be revealed. She had placed the reminders around her room — under her pillow, on the windowsill, on her dresser, between the pages of her Bible. The bulletin with Padre Luigi’s speech she placed carefully in the drawer of her dresser, where she stood each night to read it in front of her mirror before she slept, plumping her resolve.

Aurelia listened more carefully to her sisters’ complaints about their failing health. She bought extra tomatoes and gave them to her neighbour Yolanda who rarely got out since she’d developed diabetes. She smiled more readily and felt a quickening in her step. Every day Aurelia wrote another note and smiled to herself with growing self-respect.

‘Gimme a Criollo,’ Yoel says, turning to his compañero.

Yurubí jerks awake and puts a cigarette between his own lips before flipping the crumpled packet at his workmate. He reaches into his pocket for a match. He has none, neither does Yoel. They stare at each other, shrug, and return to their headsets. They’ve sat through weeks of numbing silence broken only by the clatter of pots and pans as lunchtime approaches, and on Sundays the whirr and swish of a washing machine or the slap of cloth on stone from a backyard patio.

Yoel’s body tenses as he catches the sound of soft voices under the click of cutlery. This latter makes his mouth water, filling his mind with images of plates loaded with food, like the slide projections on the wall of the Hotel Habanero on Saturday nights. Yoel’s wife has hung propaganda posters in their kitchen, but the food she serves bears no resemblance to the meats, vegetables and salads glistening with oil and drops of vinegar that loom before him. He strains to hear what the rebellious Catholics are saying — a word, just one word is all he needs — Huelga! — but there’s nothing now but a low hum broken by intermittent crackling. If only he had a match to light his cigarette, then his stomach might stop growling.

‘¡Coño! ¿Qué estamos haciendo aquí?’ he says, slamming down his headset.

Yurubí shrugs. ‘It’s a job. We’re not paid to ask questions.’

‘What if we told them we heard something?’

‘Whaddya mean?’

‘A word. You know. Strike!’

‘But I never heard . . . ’

‘I’m not talking about what you heard, imbécil! I’m talking about using our imagination, putting an end to this fucking tedious job.’

‘¡No puedo, no puedo! Soy hombre honesto,’ Yurubí protests.

‘Agh, come on, just a little white lie, compañero. People hear things all the time.’

‘No!’ Yurubí slams his fist on the table, upsetting the transmitter and disconnecting the fragile wires.

‘¡Aiee coño! ¿Hermano, qué haces?’

‘Gimme five pesos,’ Yurubí demands. ‘I’ll go buy sandwiches while you fix this.’

As Padre Luigi had boarded the morning bus to Santiago his heart was filled with the previous night’s farewells, the music of Los Huracanes pulsing still in his veins, the sad eyes of Aurelia Fernandez Pérez haunting him. From Santiago he was to fly to La Habana where he would connect four hours later with a direct flight to Milano, close enough to his hometown. It had all been arranged by the Archbishop’s office, the tickets booked, paid for, and delivered by special courier to the Casa Paroquial in Baracoa.

As the bus had rumbled along the Malecón, belching black smoke, Luigi pondered the irony of his situation so he did not at first realize what was happening. The bus slowed and came to a sudden jerking halt. Necks craned down the aisle and one or two brave souls jumped up to see what was going on. It was only when Luigi heard his name being chanted over and over that he stood up and walked to the front of the bus. They were at the corner of the Matachín Museum where the Historian of Baracoa presided over his dusty colonial relics. Ahead of them was the looming concrete statue of Cristóbal Colón. Their way was blocked by a crowd of teenagers chanting, ‘Padre Luigi, Padre Luigi!’

He had stared in disbelief, then slowly his mouth spread in a huge grin as he read the crudely scrawled posters that the children held up — TE AMAMOS PADRE LUIGI — POR FAVOR REGRESA PRONTO — SIEMPRE TE RECORDAREMOS . . . We love you Padre Luigi — please come back soon — we will always remember you . . .

It was a full ten minutes before the bus driver was able to get through. Only when he threatened to call the police had the young folk of Baracoa begun to disperse, sad but triumphant. As they waved goodbye to Padre Luigi, he noticed that many of them were wearing their SEREMOS COMO EL CHE T-shirts.

ÁNGELA DE LAS PIEDRAS

Midnight. Ángela counts the chimes of the full moon clock floating above her. She sees it dimly through the film of cloth that covers her from head to toe, clinging to the skin of her face where it quivers with each breath. She’s stashed her sack of tin cans and bottles under her bench. It takes all day to collect them from tourists slurping their beer, rum, refrescos, tossing the cans away. She’s helped the old man again. People say he’s her father, but he is not. Only that he lives free like her, sleeping outside like a dog curled in on himself. Where does he sleep? On the beach, with his own sack of garbage? Ángela has Parque Central to herself, but she has to wait till everyone’s gone home and all the tourists have stumbled back to their casas and their comfortable beds. Godofredo leaves soon as the bars close because he has somewhere to go. He shares a house with his sister — Casa Maní, they call it, because he is the peanut vendor. ‘¡Maní, maní!’ Whenever Ángela hears him calling she runs to get her peanuts. He always gives her an extra cone for free, and a nice smile. Eugenia has gone too — she leaves early with the remains of her chocolate bars and cucuruchu. She lives on Playa Caribe by the stadium. She collects wood from the beach and lights a fire in the night to cook her fish and vegetables, then she sleeps by the embers listening to the waves crashing on the sand. She is the happiest person Ángela knows. Every day the same blouse, the same skirt, but it’s her face that people see with that big smile and her teeth shining white like new grave-stones. She asks the tourists for their clothes and they laugh at her, but Eugenia doesn’t care. One day a tourist gave her a red blouse. That’s the one she wears, every day, every month, every year. The years do pass, Ángela knows. Now it’s a new one, año nuevo, another anniversary of the Revolution has passed. Last year was the lost year. They took her to the hospital in Guantánamo because she was angry with the tourists who stared at her, shooting with their cameras, shooting shooting, without her permission. ‘I am the President of Baracoa!’, she had shouted. ‘You have no right!’ They took her away over a steep winding road and forced her to sleep against her will, a long dark time.

Ángela turns slowly on the hard bench, easing her sore hip out from under. She fits perfectly. She is short, but her arms and legs are strong. Her scalp itches suddenly beneath her tangle of hair and she scratches furiously at it, digging with stubby fingers. She has a gap-toothed comb she found on the street, purple with long fat teeth — must have dropped from a tourist’s backpack, they don’t have combs like that in Cuba. On Sunday mornings she holds it above her head like a magic wand and pulls it through her hair blessing herself with the strange words she has heard coming from their mouths . . . ‘ee mael . . . deena . . . kees’ . . . Sometimes the Sisters take her in and give her a shower, scrub her skin until it shines like burnished guayacán. Sister Magdalena washes her hair, but her hands are rough and Ángela winces as her hair is pulled this way and that, but afterwards she feels good, wrapped in a towel like a little girl, her skin pink and tingling. She’s forgotten how old

she is, though she does remember those birthdays when Mami made cake and ensalada fria. She hasn’t seen Mami for such a long time. They’ve all disappeared, the people she remembers. No-one came to see her in the hospital. But she’s home now and she will visit Mami . . . in the cemetery on the hill . . . high above Baracoa . . . drifting, drifting, a warm comfortable feeling . . . legs twitching under her shroud . . . drifting into the church under the full moon clock. She must be late because the church is already full. Ángela stands at the door and watches. The people rise and sing, then they sit and listen, they kneel and bow their heads with closed eyes. Ángela marches up the centre aisle and stands before the altar staring at the bald padre with the shining head as he swings his censer. She breathes in the sweet pungent smoke. She wants more so she reaches for her pipe with the stub of tobacco sticking out of the bowl, searches in her pockets, can’t find matches. A firm hand grips her arm and she swings around ready to fight, but it’s only Sister Magdalena urging her into the Sisters’ pew in the seat at the end so she can see. Ángela’s face creases into a smile as she sits, her back curved in prayer, flaring into the roundness of a bottom that gives her ballast and fills the material of her shorts — not the tight calenticos that the jineteras wear — longer, more like a skirt. Ángela has a deep sense of modesty and when the young men in Parque Central taunt her with filthy comments about her body she screams at them, her fist slapping into her palm.

She wakes suddenly, hands clasped, her breath rapid and shallow. But no-one is there. It’s only the memory of that day when she lost herself, heard nothing but the screeching of her own voice, louder and louder, blocking out their cruel words. She’d scurried back and forth, unable to leave them be, and suddenly she’d found herself bent double over the roots of the giant mango in the middle of Parque Central, scrabbling for a stone. She’d found one, small but sharp-edged, and hauled back with her right arm ready to pitch it. Then one of the men darted over. ‘No, no!’ he’d shouted, wagging his finger at her. ‘Don’t you throw stones at me. Drop the stone, drop it!’ ‘¡Angela de las piedras!’ shouts another one, jeering at her, and they all join in — ‘¡Ángela de las piedras, de las piedras, de las piedras!’ Ángela trembles as sweat breaks out on her itching scalp. She feels the stone still clenched in her palm, remembers that night on the beach when they’d found her sleeping in the bushes and rammed their things into her, bouncing her on the hard sand. A fresh wave of anger rises. She’s lost her stone. She has no defence but her voice. The men cluster with their backs to her and she can feel the eyes of everyone in the park staring at her, but she doesn’t care. Her fury is a red tide rising with nowhere to go. She runs through the park screaming until she finds herself in front of the Casa Paroquial calling out for Padre Luigi who has blessed her and given her communion at Sunday Mass. She calls and calls, her eyes closed as she has seen the parishioners’ eyes closed in prayer. Where is Padre Luigi? Her throat aches with unshed tears. He would have given her refuge, but they’ve sent him away. ‘I am the President of Baracoa! I am a person of importance! I will not bear these insults!’ She remembers a hand on her shoulder as she turns again, restless on her bench — the smooth face of a turbaned woman hovering above her outside the Casa Paroquial. ‘Ángela,’ she had said quietly, ‘Come, my dear, I am your friend Delfina. Let us go to Casa Chocolate and eat helados. Estás invitado.’ Delfina had placed her arm lightly upon Ángela’s shoulders and suddenly all her fury had drained away, splashing around her ankles like rain. Her arms dropped to her sides and she went quietly with Delfina, a few people still staring as they walked away from the park, crossed the cobbled square in front of the Municipal Offices of Poder Popular, walking towards the Boulevard as though it were a normal day — two friends taking a stroll. The men have forgotten her. To them she is like a dog to be baited at the Sunday fights in Playita where they whip their animals into a fury and set them on each other.

The clock strikes one. Ángela is motionless except for the faint rise and fall of her covering. How can it turn from twelve to one so quickly? She has seen the waxing of the moon, a gradual thing, night after night until it is a golden ball, round as the new church clock. It has been sent, they say, all the way from Padre Luigi’s birthplace. She sees it glimmering through the film of her cloth and she feels safe. He has sent the clock to watch over her. If I had found a stone on the beach that night, she thinks, I would have pounded their heads until they no longer moved. She remembers the men as one creature with many limbs and heads, like a monster risen from the sea. After the attack she’d stopped sleeping on the beach and lay down instead under the flickering lamps of the dimly lit park. But she had not slept for many nights afterwards. Too frightened to close her eyes, she’d lain shrouded, motionless, as the scene played over and over in her mind, blasting tunnels of fury into her brain.

Ángela knows everyone in Baracoa. She’s sat in the classroom alongside fifty compañeritos, she’s worked at the pizzería washing dishes with the other staff, she goes to church every Sunday, she knows them all. But she has not told anyone what happened to her, not even Delfina or Sister Magdalena. Especially not the Sisters. Who would listen to a girl who’s been in the hospital in Guantánamo? ‘Am I to blame?’ she whispers. ‘Is there something about me that frightens people, something that makes men attack me in the night?’ She remembers from school the words of José Martí — Patria es humanidad. Ángela smiles as she holds the echo of that word in her mouth — humanidad. A good word. A secret. When daylight comes I will be safe, she thinks. I will lift another stone and raise my voice to God.

I, GERTRUDIS

July 2012

‘My name is Gertrudis. I have lived in Santiago de Cuba all my life. I was twenty-two years old when the revolutionaries attacked the Moncada Barracks. They came to our hospital — the Saturnino Lora Military Hospital behind the Barracks. They were led by Abel Santamaria. Another group attacked the Palacio de Justicia, and they were led by Raúl Castro who was a young man then. Now he is eighty-one years old, like me, and he talks of stepping down from the Presidency of Cuba at the end of his next term.’ Gertrudis leans forward in her cane-seated balánce and fixes her visitor with all the intensity of her cloudy brown eyes.

‘I was working on the early morning shift and I saw them burst in, running down the corridor — Abel, his sister Haydée, Melba Hernandez right behind her, and the others tumbling after. It was as though they were an avalanche of stones and pebbles rolling to earth. I saw how terrified they were as they ran past me, and it made me afraid of what was to happen. I was newly graduated as a nurse, and six months married to Ramón. We had made love that morning, in the half light as dawn was gathering to break. I was full of him still — my Ramón with his big square hands all over my body, his soft lips pressed on mine, becoming hard and insistent as he entered me.’

The visitor drops his eyes and studies the floor, embarrassed by her frankness.

‘No, that’s not what you want to hear,’ Gertrudis says, smiling to herself as she crosses the room, her gait slow and arthritic. She enters the kitchen and pours two cups of strong coffee from the freshly brewed pot, adding generous spoonfuls of sugar, stirring.

‘Moncada: Siembra Gloriosa; Siempre es 26 — primer impulso; 26 de Julio, Batalla de las Ideas; Un Mundo Mejor es Posible,’ she recites loudly on her journey back to the sala. ‘Signs all over the countryside surrounding Santiago de Cuba, on the highway to Guantánamo, to Baracoa, and probably all the way to La Habana.’

The visitor observes her knotted fingers as she places a coffee cup in his hands. He looks up into her face, nodding a thank you. She is a handsome woman with the kind of beauty that endures until the end because it rests on good bones and a good heart. He watches her trundle across the sala, the little cup rattling in its saucer as she places it carefully on the table beside her rocker.

‘I have never been to La Habana. I am a Santiaguera, born in Oriente, in this cradle of the Revolution.’ She sinks heavily in the chai

r, setting it in motion. ‘26 de Julio siempre — always, always that day echoing through our nation, fifty-nine years past, another anniversary coming up, and must I speak yet again, to give my testimony of that dreadful day at the hospital? Siempre, siempre, always on my mind, shaping my thoughts. Will you never let me forget?’

He raises a hand as though to stop her, but Gertrudis continues with a sweep of her arm. ‘The rebels demanded patients’ uniforms. I stood against the wall while our ward sister delved into the laundry hampers to find enough gowns and bandages until we had them all outfitted, lying in beds and on trestles. For that day we turned our hospital into a refuge. We stopped caring for the sick and harboured the revolutionaries, pretending to care for them as they pretended to be patients. It was Sister herself who denounced them. I was watching her face. I’d seen the conflict raging inside her, the pain in her expression as she said, Yes, yes, they are here, in that bed, and that one, and that one. I am a Seventh Day Adventist. I am forbidden to lie. Please do not harm them. This is a hospital, a place of healing.’

Gertrudis shakes her head, her steel-grey hair stiff, hardly moving on her brown scalp. He detects liver spots on her hands, but her cheek is smooth, almost like that of a girl, he thinks. Because she is plump and will never have the withered, scrawny look of some old women.

‘Batista’s men dragged them one by one, ripping the pyjamas and bandages off them. They were silent, so silent as they were taken away. And we were silent too until they were gone from our hospital, and then we broke into excited chatter. Some of us were weeping. We didn’t know why. We didn’t know what it was about, then one of the girls said, it’s the rebels, Fidel Castro and his followers. Pappy talks about them. He says they’re trying to save Cuba from Batista.’

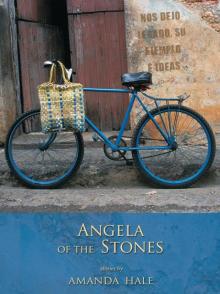

Angela of the Stones

Angela of the Stones